The Coercion of the Trial Penalty

By Kristen Akin, M.A. | Blueprint Trial Consulting

Introduction

Prosecutors, defendants, and defense attorneys must make decisions as to whether to accept a plea offer or proceed to trial every day. Approximately 95% of state and federal convictions result from guilty pleas.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 Some estimate this number to be as high as 97% to 99%.7,9 It is also estimated that every two seconds, a defendant pleads guilty.9 In 1980, 19% of federal criminal cases went to trial, but by 2010, this number was at less than 3%.4 In theory, plea deals are enticing, as they put into place safeguards for defendants rather than the uncertainty that comes with going to trial. Therefore, plea bargains give defendants the opportunity to choose between the certainty of a specific amount of time in jail, probation, or a lesser charge, as opposed to taking their case to trial with unknown outcomes. On the other hand, by accepting a plea deal, defendants waive their rights to silence, the prosecution proving their guilt, and the opportunity to confront their accusers, among other rights.1,9,10 Nevertheless, a defendant who chooses to go to trial has been shown to receive on average about nine times more severe of a sentence than guilty plea sentences.11 Given this trial penalty, most defendants who choose to go to trial face can make even the innocent feel coerced to take plea deals.

Previous studies have investigated whether innocent defendants are less likely to accept a plea bargain or which specific demographic factors may lead to some defendants accepting a plea bargain over others.1,4,5,8,12,13 Recent research focusing on whether the practice of plea bargaining may be coercive investigates public perceptions or prosecutorial efforts to coerce the defendants.2,10,14 This study investigates whether defendants feel coerced to accept a plea bargain to avoid an increased sentence they may face at trial, the trial penalty. To date, there has been little empirical work exploring the trial penalty and its possible coercive nature.

Methods

Study participants were recruited from Prolific, a website that allows researchers to connect with participants via online surveys. To participate in the study, prospective respondents had to have been able to read English and be over the age of 18. If the participant accepted, the survey continued to the questions.

To begin the study, participants were presented with one of two versions of a hypothetical crime. Within the hypothetical scenario, participants were asked to either assume the role of someone who committed a crime, or someone who was wrongly accused. The story described an armed robbery of a jewelry store, loosely based on stories from Redlich and Shteynberg (2016) and Edkins (2011).4,5 Within the guilty story, information about the gun that was used as well as eyewitness evidence of the crime were included as pieces of evidence that respondents could possibly use against the defendant. Alternatively, in the innocent version of the story, participants were told to imagine that they live alone and were “at home playing video games” at the time of the robbery. The innocent condition also contained eyewitness evidence of the incident, but no gun was recovered by the police.

In both conditions, participants were told that they would be offered a plea deal of two years. This length of time was derived from a metaanalysis performed by McCoy (2005) which found the average prison sentence length for guilty pleas of serious felony cases was 23.6 months, almost two years long.11 Additionally, in both conditions, participants were notified that if they chose to go to trial they could serve up to, in a randomized order, either two, five, 10, 15, or 20 years of jail time. These times were chosen as the United States Sentencing Commission (2015) reported 111 months is the average prison sentence for robbery, which is a little over nine years.15 Therefore, sentence lengths were chosen to realistically mirror those given as plea options for an armed robbery.

After participants were presented with each of the above stories, they were asked a series of questions to assess their general perceptions of fairness and coercion. Specifically, participants were asked whether they will accept or decline their plea deal and why they made this decision. Participants were then asked questions such as “How firm were you in your decision to either accept or decline the plea deal?” and “How severe do you feel the possible outcome of trial is compared to the plea bargain?”, all assessed on an 11-point scale from 0=Not at all to 10=Very.16 Next, participants were asked to reflect on how the jail sentence, if they choose to go to trial, would affect their life after serving their sentence. This included collateral consequences such as gaining employment, education, and general success, as well as their family life and overall happiness post-confinement.8

Finally, participants’ levels of coercion and fairness were assessed in response to the hypothetical crime using questions adapted from two separate studies. The first, a study by Bergk et al. (2010), focused on perceived levels of coercion during coercive interventions in psychiatry, or practices used to pressure or force someone into accepting treatment.17 Questions included “I felt there would be restrictions to my autonomy” and “I felt there would be restrictions to my interpersonal contacts”. Additionally, questions assessing respondents’ perceived fairness of their hypothetical prison sentence were based on a study performed by VanYperen et al. (2000). In the current study, participants were asked to respond to the statement “I felt the possible jail time if I chose trial is not proportionate with the crime”. All coercion and fairness questions were assessed on an 11-point scale, from 0=Not at all to 10=Very.

Lastly, participants’ demographics, including their age, gender, and racial/ethnic background, were assessed. The survey concluded with a short debrief describing the purpose and importance of the study.

Results

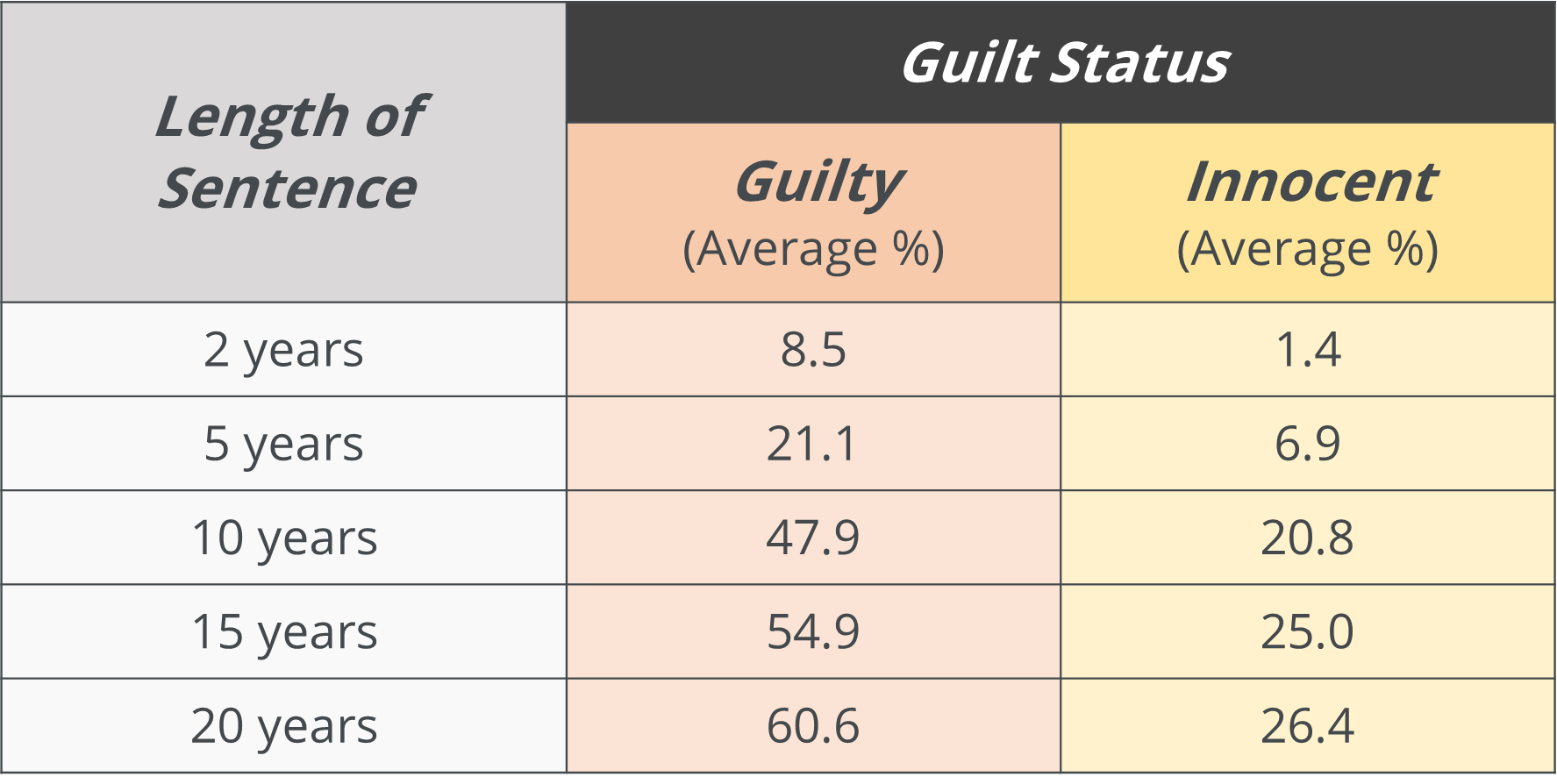

To assess the results of this study, multiple analyses were performed on the data. Firstly, we conducted a mixed-effects ANOVA to assess the relationship between guilt condition (guilty or innocent), the between-subjects factor, and sentence length (two, five, 10, 15, or 20 years of jail time), the within-subjects factor. The results revealed a significant main effect of severity of sentence length at trial, F(4,564) = 46.51, p < .01, ηp2 = .25, such that as the severity of the potential sentence at trial increased, the likelihood of accepting a plea also increased. There was also a significant main effect of guilt status, F(1,141) = 19.66, p < .01, ηp2 = .12, such that participants in the guilty condition were significantly more likely to accept a plea than those in the innocent condition. See Table 1 for the percentages of participants who accepted a plea in the innocent and guilty conditions, at five levels of sentence length at trial.

Table 1. Average percentage of participants in the guilty and innocent conditions who accepted pleas when faced with five levels of sentence exposure at trial.

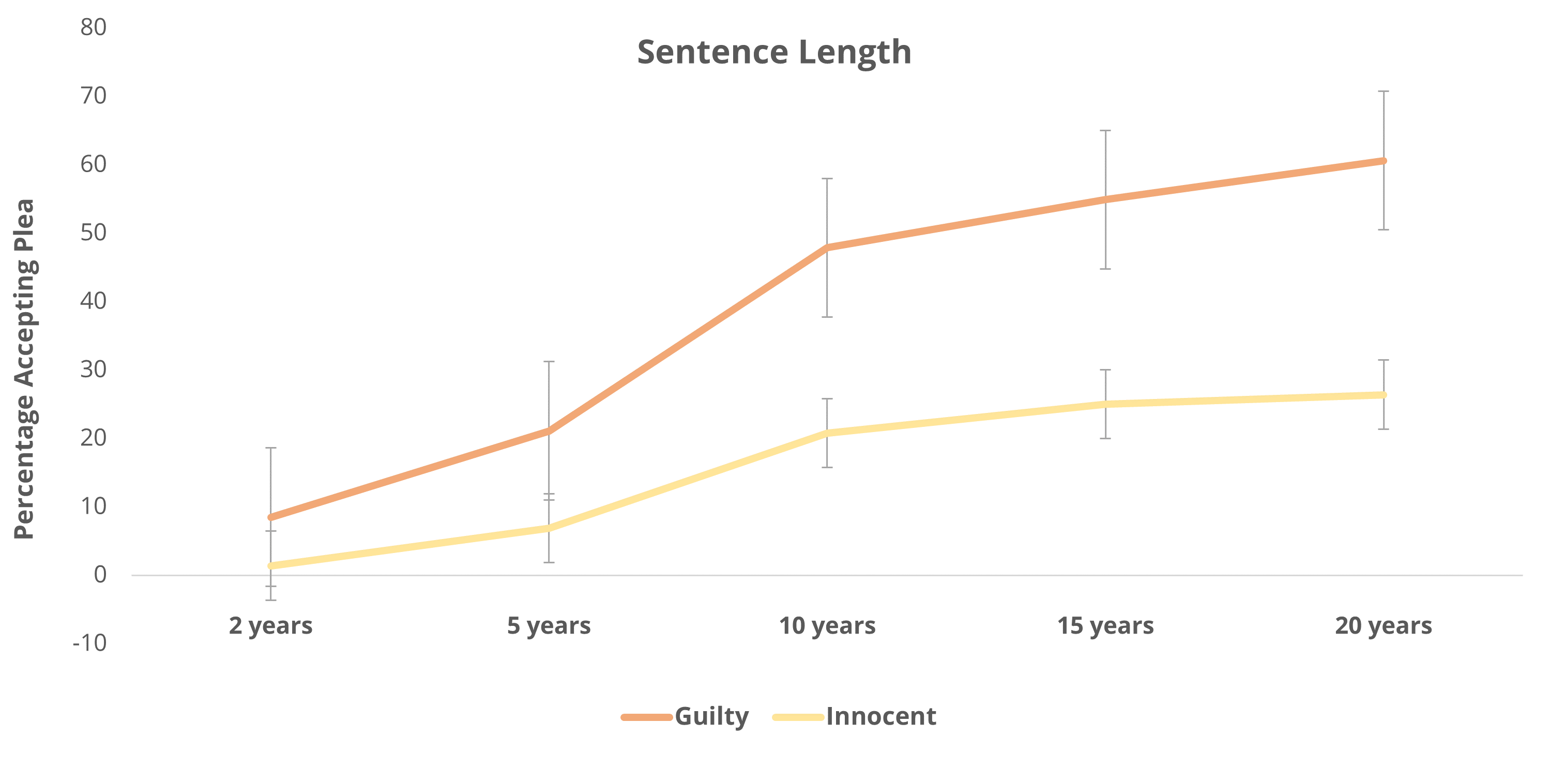

Also shown from the mixed-effects ANOVA, a significant interaction between sentence length and guilt status, F(4,564) = 5.26, p < .01, ηp2 = .04. That is, as the severity of potential trial sentence grew more severe, although both innocence and guilty people were more likely to accept a plea, those in the guilty condition were even more likely to accept it than those in the innocent one as the severity increased. See Figure 1 below a graphical representation of this interaction effect.

Figure 1. Percentage of participants who accepted pleas in innocent and guilty conditions, at five levels of sentence exposure at trial.

After deciding whether they would accept or decline the plea based on the vignette presented to them, participants answered two free-response questions to elaborate on their decision. These responses were qualitatively analyzed by categorizing them according to their content and theme.

The first question asked participants to explain why they chose to accept, decline, or were unsure of whether to accept or decline the plea deal. The most common argument for those who decided to accept the plea was that the plea bargain was better than the possible time that the person could face at trial. Furthermore, participants chose to accept the plea because they had committed the crime (specific to those respondents in the guilty condition), thought they would probably be convicted at trial, and/or because they did not have an alibi.

Alternatively, the most frequent argument made by those who decided to decline the plea bargain was that there was little evidence/weak evidence to prove their involvement. Other common reasons included that they did not commit the crime (specific to the innocent condition), eyewitness testimony is unreliable, and/or they did not think the prosecution could prove their involvement beyond a reasonable doubt.

In the second free-response question participants answered, they were asked to describe specific factors of the vignette that affected their decision to accept the plea bargain or not. Among participants who accepted the plea deal, they most often invoked arguments such as the perceived strength of the eyewitness evidence, and that they are guilty when favoring accepting the plea deal. Comparatively, participants who favored denying the plea deal most often reasoned that the evidence in the vignette was weak or lacking, that the eyewitness testimony was unreliable, and/or that they were innocent.

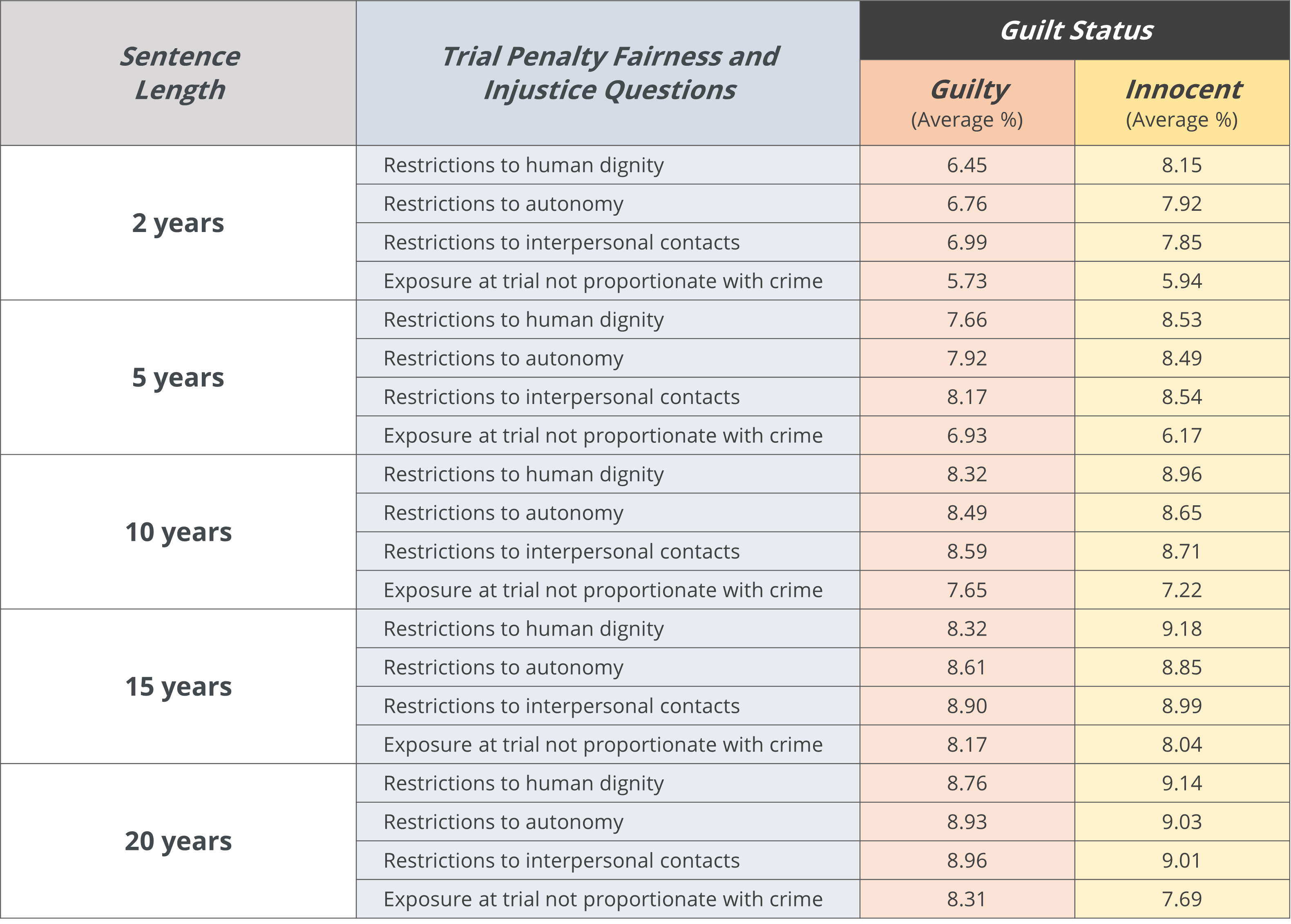

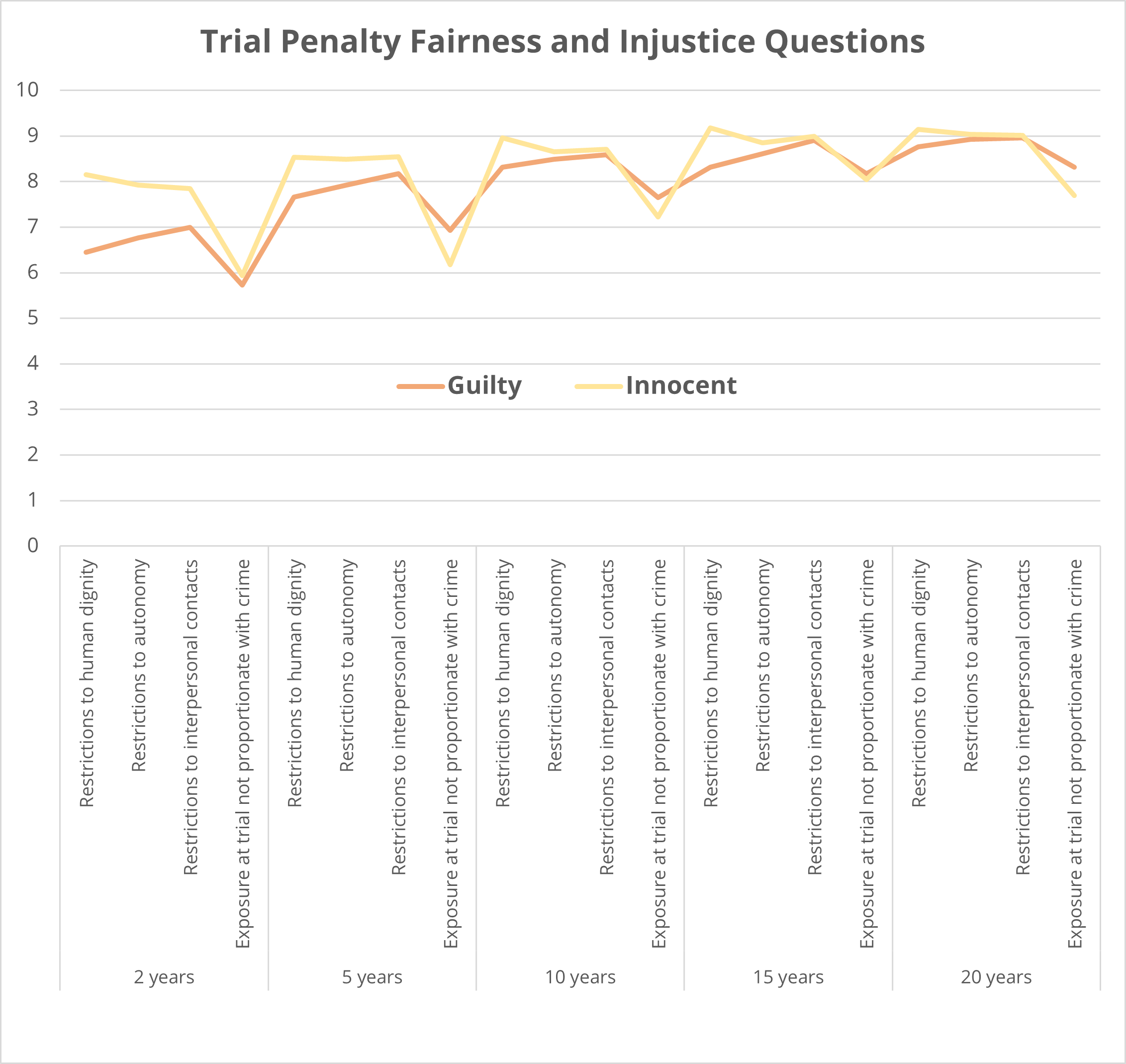

Furthermore, an independent samples t-test was run to compare the average of respondents’ perceived fairness and injustice on four fairness and injustice questions at each year presentation with the between-subjects variable of guilt and innocence. This t-test showed that when both the plea bargain and the possible time they could face at trial was 2 years, participants in the innocent condition reported a statistically significant greater average restriction to their human dignity (M = 8.09, SE = .3) than those in the guilty condition (M = 6.54, SE = .36), t(132) = -3.26, p < .01. Those in the innocent condition also reported a statistically significant greater average feeling that there would be restrictions to their autonomy (M = 7.88, SE = .32) compared to those in the guilty condition (M = 6.88, SE = .38) when both the plea bargain and the possible time they could face at trial was 2 years. This difference was significant, t(131) = -2.0, p = .05. See Table 2 and Figure 2 below for the average responses to these questions by participant in innocent and guilty conditions.

Table 2. Average responses to fairness-related questions assessed on an 11-point scale (0=Not at all and 10=Very) for guilty and innocent participants at five levels of sentence length at trial.

Figure 2. Means for four injustice and fairness questions over different sentence exposure conditions.

Conclusion

In the present study, I analyzed feelings of coercion and injustice associated with the trial penalty, which to my knowledge has yet to be done. I was also interested in examining how differences between the possible time at trial and the plea bargain could affect plea decisions, as well as defendants’ feelings of coercion and injustice. Overall, I found that as the hypothetical trial penalty increased, participants were more likely to accept the plea bargain, and even more likely to do so in a guilty versus innocent condition.

To my knowledge, the present study is the first to examine feelings of coercion and injustice associated with the trial penalty.

However, this study does present with some limitations. Firstly, data collection was done through Prolific which allowed for a more diverse data collection than a student population. On the other hand, these participants were not faced with the reality of the situation that the hypothetical innocent and guilty stories portrayed. Additionally, the demographic makeup of those who responded on prolific is different than those who are in the United States prison system.19

Overall, generalizability of this study should be taken into account upon reading these results. This study is a promising start to assessing how plea bargains, and subsequently the trial penalty, can be unjust and unfair even to those who are innocent. As shown in this study, the coercive nature of the trial penalty can entice the innocent as well as those who are guilty to relinquish their rights of a fair trial for a lesser sentence which can be served beginning immediately. Furthermore, it seems past a certain point, possibly a difference between plea bargain and sentence exposure of about 10 years, feelings of injustice and unfairness somewhat neutralize between those who are guilty and those who are innocent. Although those who are innocent seem to still accept the plea bargain less often than those who are guilty, feelings of injustice and unfairness seem to be greater when the difference between the plea bargain and sentence exposure are less. Further research should be done to verify these results with a more generalizable population.

References

- Redlich, A. D., Bibas, S., Edkins, V. A., & Madon, S. (2017). The psychology of defendant plea decision making. American Psychologist, 72(4), 339–352. https://doi-org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/10.1037/a0040436

- Thaxton, S. (2013). Leveraging Death. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 103(2), 475-552.

- Gazal-Ayal, O., & Tor, A. (2012). THE INNOCENCE EFFECT. Duke Law Journal, 62(2), 339-401. Retrieved March 26, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23364853

- Redlich, A. D., & Shteynberg, R. V. (2016). To plead or not to plead: A comparison of juvenile and adult true and false plea decisions. Law and Human Behavior, 40(6), 611–625. https://doi-org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/10.1037/lhb0000205

- Edkins, V. A. (2011). Defense attorney plea recommendations and client race: Does zealous representation apply equally to all? Law and Human Behavior, 35(5), 413–425. https://doi-org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/10.1007/s10979-010-9254-0

- Weatherly, J. N., & Kehn, A. (2013). Probability discounting of legal and non-legal scenarios: Discounting varies as a function of the outcome, the recipient’s race, and the discounter’s sex. Behavior and Social Issues, 22. https://doi-org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/10.5210/bsi.v22i0.4717

- Helm, R. K., Reyna, V. F., Franz, A. A., Novick, R. Z., Dincin, S., & Cort, A. E. (2018). Limitations on the ability to negotiate justice: Attorney perspectives on guilt, innocence, and legal advice in the current plea system. Psychology, Crime & Law, 24(9), 915–934. https://doi-org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/10.1080/1068316X.2018.1457672

- Gregory, W. L., Mowen, J. C., & Linder, D. E. (1978). Social psychology and plea bargaining: Applications, methodology, and theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(12), 1521–1530. https://doi-org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/10.1037/0022-3514.36.12.1521

- Redlich, A. D., & Bonventre, C. L. (2015). Content and comprehensibility of juvenile and adult tender-of-plea forms: Implications for knowing, intelligent, and voluntary guilty pleas. Law and Human Behavior, 39(2), 162–176. https://doi-org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/10.1037/lhb0000118

- Joselow, M. (2019). Promise-induced false confessions: Lessons from promises in another context. Boston College Law Review, 60(6), 1641-1688.

- McCoy, C. (2005). Plea bargaining as coercion: The trial penalty and plea bargaining reform. Criminal Law Quarterly, 50(Issues 1 & 2), 67-107.

- Tor, A., Gazal‐Ayal, O. and Garcia, S.M. (2010), Fairness and the Willingness to Accept Plea Bargain Offers. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 7, 97-116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-1461.2009.01171.x

- Jones, S. (2011). Under pressure: Women who plead guilty to crimes they have not committed. Criminology & Criminal Justice: An International Journal, 11(1), 77–90. https://doi-org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/10.1177/1748895810392193

- Khogali, M., Jones, K., & Penrod, S. (2018). Fairness for all? Public perceptions of plea bargaining. Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice, 14(2), 136-153.

- United States Sentencing Commission. (2015). Quick Facts Robbery Offenses. https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/quick-facts/Robbery_FY15.pdf

- Bordens, K. S., & Bassett, J. (1985) The Plea Bargaining Process From the Defendant’s Perspective: A Field Investigation. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 6(2), 93-110. doi: 10.1207/s15324834basp0602_1

- Bergk, J., Flammer, E., & Steinert, T. (2010). “Coercion Experience Scale” (CES)—Validation of a questionnaire on coercive measures. BMC Psychiatry, 10. https://doi-org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/10.1186/1471-244X-10-5

- VanYperen, N. W., Hagedoorn, M., Zweers, M., & Postma, S. (2000). Injustice and employees’ destructive responses: The mediating role of state negative affect. Social Justice Research, 13(3), 291–312. https://doi-org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/10.1023/A:1026411523466

- Federal Bureau of Prisons. (2022). Inmate Race. https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_race.jsp